A Week in Gastronomic Paradise

What is the ultimate French food experience? Shopping in a Paris open-air market? Spending the afternoon in a sidewalk café on a spring day? Savoring every moment of a dégustation at a three-star restaurant? Nope! The ultimate French food experience lasts an entire week. It involves two meals a day from a Michelin–starred restaurant. It includes spending time with a Michelin–starred chef learning the tricks of the trade. It involves visiting food and wine producers and observing the intimate workings of their production. It may even involve visiting a market or two.

And I just got back from France where I had this ultimate experience. It started this way one Sunday last June…

I met up with six other "foodies" at the train station in Besançon, in the heart of Jura region of France. My fellow travelers included two cooking instructors from Paris, an artist from Maryland, an ENT surgeon from Minnesota, a retired business man from Washington, DC, and Patti Ravenscroft, founder and director of Les Liaisons Délicieuses, which organized of our adventure.

From Besançon we drove 30 kilometers southwest to the small village of Amondans — home of the 18th-century Château d’Amondans — our home for the next week and site of a Michelin 1-star restaurant under the direction of Frédéric Médigue.

Meeting new people, especially en masse can be stressful. After the prerequisite bonjour monsieurs and madames at the Château gates, we reconnoitered our rooms, unpacked, and then gathered outside in the Château’s extensive garden for an aperitif — the first of many we would enjoy during the week.

Before sitting for dinner, Patti took us on a quick tour of the Château’s expansive, modern kitchens. The kitchen includes separate areas for hot and cold final cooking and assembly, fish and meat preparation, and baking and desserts.

Dinner that night, as on all nights, was served in one of the Château’s spacious and luxurious dining rooms. Always present are unique flower arrangements made from the pickings of the Château’s own gardens and skillfully arranged by Pascal, the headwaiter.

Dinner followed the same routine that one would expect in one of France’s 479 Michelin-starred restaurants. A plate of hors d’oeuvres is presented the table to start the meal. (At Château d’Amondans this consists of a wafer of puff pastry baked with a topping of the local Comté cheese along one edge.) The first individual course is the entrée. This is followed by the plat, then the cheese course, and finally the dessert. Occasionally, a small amuse-bouche precedes the entrée. The dessert is accompanied by a plate of les mignardises, small sweets. (At the Château, the sweets were miniature eclairs, profiteroles, madeleines, lemon tarts, and candied orange peel.) Finally, the meal is completed by coffee or tea. As great as our first meal was, we would soon learn that each meal in turn would outshine the previous one. Recipes were provided for many of the dishes, but it is always necessary to revise and modify the original ingredients and instructions for the American kitchen and ingredient availability.

For me, the best part of the week was spent in the kitchen. Sometimes Chef Médigue would demonstrate a particular dish. Other times the emphasis would be on a particular group of techniques. Often, I would just wander into the kitchen to observe the various stages of the process of preparing fine meals. If there was something that I didn’t understand, the Chef was always willing to provide a suitable explanation of what was happening. If I wanted to know how a particular dish was prepared, Chef Médigue would recite the process, and I would hurriedly scribble notes and snap a few pictures to document the process. It will be months before I can try at home all I learned in that one week.

The night that the Château was closed for business; we were guests at a one–star restaurant in Besançon called Mungo Park. This proved to be a wonderful evening and the meal was outstanding.

But the week wasn’t all eating and cooking. Once we visited a local winery that produces the special Jura wines. The Château provided lunch and the winery provided the wine. In all we tasted nine different wines. Another time we visited a producer of Comté cheese. We also went to the local market in Besançon one morning with the Chef — although he admitted that he didn’t have time to go to the market everyday — he just ordered what he needed from local suppliers that he had dealt with for years and could trust to provide ingredients of exceptional quality. After the market we visited a local patisserie that produced world-class pastries, chocolates, and ice creams.

We also spent some time touring the region and enjoying the sights. The Jura is really a forgotten part of France in the foothills of the Alps. There’s great natural beauty plus charming villages — such as Ornans and Arbois — and interesting historical sites — such as the Château de Joux.

Saturday morning came much too quickly. After a coffee and croissant, the group headed for the train station and went our separate ways. We had had a wonderful week of food and fun, but I don’t think any of us could have looked at another one of those glorious, beautiful, rich, elaborate meals for a while!

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Although Louis Pasteur was born in Dole, his true home in the Comté was the town of Arbois. After his parents moved there in 1827, he spent his youth there, his parents died there, and to the end of his days Pasteur never failed to spend his holidays in Arbois. When the Pasteur family moved to Arbois, they settled in a tannery which the scientist later turned into a large comfortable residence. The father did all types of leather work; the mother ran the household, raised the children, and kept the accounts. The close family life in which a high moral code was adhered to marked the young Louis for life.

He attended primary school, then secondary school (where the sundial he made is still in the school yard). He was a conscientious, serious worker, who devoted so much careful thought to things that he gave the impression of being rather slow, and he was never considered more than a slightly above average student. His greatest interest was drawing. He drew portraits in pastels and pencil of his parents and friends, in which a certain talent is apparent. To be able to study for his baccalaureate, the young man entered the grammar school of Besançon as a teaching assistant.

With his admission to the Ecole Normale in 1843, Pasteur embarked on the career which was to distinguish him as one of the greatest minds in the history of mankind. He began with the study of pure science, where his studies of the geometry of crystals soon attracted attention. He then turned to practical problems. His study of various types of fermentation led him to discover the “pasteurization” process by which wine. beer and vinegar could be prevented from going off his work on the illnesses of silkworms were invaluable to the silk industry. He produced vaccines to cure rabies in man and anthrax in animals. He put forward theories in the held of microbiology which were to revolutionize surgery and medicine in general, leading to the use of antiseptic sterilization, and isolation of those with contagious diseases. Pasteur also paved the way for immunization therapy (using antiserums).

The house where Pasteur spent his youth [in Arbois] has been preserved in such a way that visitors might almost think the great scientist was still in residence. The penholder stands ready on the desk: the inkwell and blotting pad are in their usual place; the cap might have been taken off just a few seconds ago. Photographs recall the faces of those Pasteur loved. The instruments and apparatus used by the illustrious scientist during his stays in Arbois are on display in the laboratory. Even the culture mediums, which he used for his experiments on spontaneous generation have been preserved.

Excepted from Burgundy-Jura (Michelin Green Guide) 1995.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The 18th century Château d’Amondans viewed from the garden

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

This château reigns over the extreme end of the Pontarlier cluse, used since the Roman Empire as a route linking northern Italy with Flanders and Champagne. This great trade route also served for invading forces: Joux was besieged by the Austrians in 1814, and by the Swiss in 1815; the fortress was used to cover General Bourbaki’s army in 1871, on its retreat into Switzerland; and the German invading army used it in 1940.

The chateau was built by the Lords of Joux in the 11 C, and was enlarged under Emperor Charles V. Vauban fortified it, in view of its vulnerable position near the border, after France annexed the Franche-Comte in 1678, and the fortress was used as a prison until 1815. The last modernizations were carried out between 1879 and 1881, by the future field marshal, Joffre. The stronghold has seen many political prisoners, military figures and other famous personalities pass through its gates. Mirabeau was shut up here after his father, tired of bailing his son out of the debts he ran up with his profligate lifestyle, succeeded in obtaining an order under the King’s seal to lock him up out of the reach of moneylenders. Toussaint Louverture, a black politician who played a major role in the fight against slavery in France, earned Napoleon’s displeasure with his efforts to win independence for Haiti and was imprisoned in Joux in 1802. He died of a lung infection a couple of months later, thus missing the proclamation of Haitian independence read out by Dessalines on 1 January 1804. The German writer Heinrich von Kleist was also held here on charges of spying in 1806.

Excepted from Burgundy-Jura (Michelin Green Guide) 1995.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

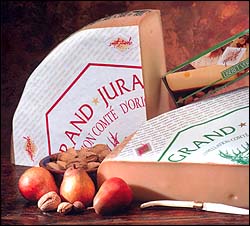

Cheese, the pride and joy of the Jura

Cheese is a direct product of the significant amount of stock-breeding there is in Jura, and the dairy industry represents a major proportion of the region’s economy. This used to be a family industry, which evolved in step with that of stock-breeding during the 19C. It grew more refined with more rigorous selection of stock, rationalization of working methods, modernization of equipment and by professional organization of the dairy industry from family cooperatives to associations and finally to companies. Nowadays, a professional cheese-maker will usually rent a cheese dairy (“fruitière”) in one of the villages, buy in his milk and sell the finished product on; warehouses for maturing cheese have been set up in larger towns and cities.

Cooperative cheese dairies: The production of Comté Gruyère cheese is one of the major industries on which the economy of this region depends. This production is based on the “fruitière”, or cooperative cheese dairy, formed by the milk producers of one or more villages. This is one of the oldest and most traditional features of life in the Jura. A cooperatively made cheese, “froumaige de fructères” (fromage de fruitière), was being produced in the Doubs uplands in as early as 1264. Cooperative production was essential in areas where adverse weather conditions frequently made travelling difficult, if not impossible during winter. The number of cows per producer is tending to increase (10 to 20, and sometimes more), and the amount of milk produced by each cow is almost 876 gallons on average for every 300 days lactation. It takes 131 gallons of milk to make a 165 lb Comté Gruyère cheese.

At milking time, you still see women, children and the occasional man heading towards the cooperative dairy, carrying their milk in buckets, milk-cans, on the back of a donkey, in hand-carts or dog-carts, or even using more up-to-date means such as trailers pulled by tractors or motorcycles, or in small vans. In times gone by, the very basic modes of transport limited the dairy’s catchment area and consequently the number of members of the cooperative, which was never more than fifty. Nowadays, however, the system for collecting milk has tended to favor larger cheese dairies, leaving the smaller ones to decline in numbers. Nonetheless, the traditional twice daily milk delivery has to survive, as it is fundamental to a certain quality of cheese.

How Comté cheese is made: “Comté” is a registered product subject to quality control. The cheese is made from the milk of Montbéliard stock or red and white cows from the east of France, which have been fed exclusively on grass and hay. The milk is skimmed of 5-15% of its cream content to produce a cheese which has a fat content of about 48-50g per 100g of dry mass. The milk is then poured into huge copper cauldrons, with a capacity of 177, 311 or 555 gallons, where it is heated to about 90 °F and curdled with rennet. It is then drained, and the curds are beaten and heated to between 129-133 °F, put into a linen cloth, placed into a mould and then pressed. The resulting round of cheese can weigh up to 88-110 1b. The cheese is put into a cold cellar for a few days, where it is salted and rubbed to speed up the formation of the rind. After this, the maturing process begins. The cheese is kept for three to nine months maximum in a cellar, initially at a temperature of 60-65 °F for two months, and thereafter at between 5O-54 °F. The rind is rubbed with a cloth soaked in salt solution to encourage the growth of the moulds which give the Comté cheese its characteristic hazelnut flavor.

The uninitiated believe that the more holes there are in a Gruyère cheese, the better it is. However, this is certainly not the case with Comté. The finest, richest Comté cheese is that with no (or at least, very few) holes.

Other cheeses: Morbier cheese comes from Morez and the surrounding area, while the blue cheese Bleu de Haut-Jura comes from Septmoncel and Gex. Vacherin or Mont d’Or is a soft cheese made during the winter in the region of Champagnole, which was already being savored in Levier in the 13C. Since 1917, factories at Lons-le-Saunier and Dole have been manufacturing various processed cheeses based on pasteurized pressed cheeses (Emmenthal, Gruyère, Comté), pasteurized non-pressed cheeses (Cheddar, Gouda, St-Paulin and Cantal) and blue cheeses (Roquefort, Bleu), and in the manufacture of which other dairy products such as butter, cream and milk may be used.

Excepted from Burgundy-Jura (Michelin Green Guide) 1995.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Along with an aperatif, a plate of puff pastry wafers with one edge coated with comté cheese was presented before each meal.

To create Feuilleté au Comté:

- Roll out puff pastry to thickness of 1/4 inch. Sprinkle with a single layer of grated comté cheese. Roll to a 3/16 inch thickness pressing cheese into surface. Freeze until firm.

- When hard, cut into 3/8 inch wide by 6 inch long pieces and return to freezer.

- Preheat oven to 410 °F.

- Place frozen dough on a prepared baking sheet. Allow sufficient space for dough to expand while baking. Bake until puffed and cheese begins to melt, about 15 minutes. Serve warm.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Each meal, between the plat and dessert, a large cutting board with a selection of about a dozen regional cheeses was brought to the table. Each of us would select those cheeses we wished to taste.

On the last evening, four different Roqueforts were brought for us to taste. All the Roqueforts were from the same region, but tasted distinctly different. (A nice Port was served to make the Roquefort taste even better.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Chef Médigue demonstrated the classical method of cutting a whole chicken into serving pieces. This included a technique for removing the tendons from the legs — which cannot be done in the United States because the chickens sold here lack the next joint with the tendons attached. Unlike the standard American method of dividing the breast which produces two pieces of white meat, the French method produces five pieces of white meat. Note that it also helps to start with a larger chicken than our three pound fryers.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

émietté de crabe à l’huile de curry

Potato Chips:

- Using a mandolin, thinly slice a white potato no thicker than 1 mm. Cut slices into right triangles, 3 by 6 cm. Six are required for each serving.

- Place slices on oiled, non-stick baking sheet. Lightly brush the top surface with olive oil. Sprinkle each potato triangle with fine salt and paprika.

- Bake until potato slices start to brown in a 385 °F oven.

- Set aside to cool.

Leek Strips:

- Using a small leek, about 2 cm in diameter, cut and clean a 6 to 7 cm long section of the white portion. Make a single lengthwise cut to center and lay out the layers of leek flat on a cutting board. Julienne lengthwise very, very thinly.

- Separate leek strips and soak in ice water until curly. Drain well on paper towels and set aside.

Chives:

- Cut chives into 7 cm long pieces and set aside.

Crab:

- Prepare a court bouillon using wine, carrots, onions, celery, and water. Bring to a boil and add orange zest, star anise, white wine, and vinegar.

- Bring to a boil again. Add live crab and cook for 1 minute. Remove and set aside to cool.

- When cool, remove meat from crab and shred.

Sauce:

- Combine turmeric and curry powder with olive oil. Let infuse over night.

- Strain the infusion through a kitchen towel and set aside flavored-oil aside. Discard spices.

- Reduce balsamic vinegar by half and set aside.

Mayonnaise and Crab Mixture:

- Mix an egg yolk with an equal amount of Dijon mustard. Make a thick mayonnaise using grapeseed oil. Finish with a small amount of olive oil, salt and wine vinegar.

- Combine mayonnaise with an equal amount of shredded crab. Set aside.

Avocado Mixture:

- Peel and seed an avocado. Place in the bowl of a food processor, add lemon juice and 1/4 teaspoon garlic purée.

- Process with olive oil into smooth purée. Season with Tabasco sauce and salt. Set aside.

Assembly:

- Place a 6 cm diameter ring mold on the center of a serving plate. Fill two-thirds full with the avocado mixture. Level surface and fill with crab mixture. Level surface. Carefully remove mold straight up.

- Place 6 potato chips as spokes in crab-avocado mixture.

- Fill space between chips with leeks. Top with chives.

- Drizzle sauce around arrangement.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The following are examples of some of the desserts served by Chef Médigue during the week at the Château d’Amondans…

macaron, crème de pistache et framboises du pays raspberry tart with a macaroon base and pistachio cream, served with a fresh sorbet and puréed raspberries

omelette flambée norvégienne two sorbets with an Italian meringue crust flamed with rum

cerise jubilé cherries “jubilee” served with cherry sorbet and a crumbly cookie

pêche melba stewed peach served with fresh vanilla ice cream

samouraï mousse cake with passion fruit sorbet

gateau moelleux chocolat pistache chocolate cake with a soft pistachio cream center

gratin de cerises sorbet de bourgeons cassis baked cherries in custard with sorbet of red currants

tarte aux pêche fresh, warm peach tart with peach sorbet

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The following are examples of some of the entrées (first courses) served by Chef Médigue during the week at the Château d’Amondans…

terrine de toureau aux coulis de tomates terrine of crab served on a fresh purée of tomatoes

salade de pain aux langoustines et basilic puréed salad of bread and tomatoes with Dublin Bay prawns and balsamic vinaigrette

aigo sau Provençal fish soup

terrine de truite et saumon fumé aux pommes de terre terrine of red trout and smoked salmon with potatoes, pickles, and apples

terrine de foie gras de canard aux morilles terrine of fattened duck liver and morel mushrooms

gaspacho de langoustines cold soup of tomatoes, cucumber, sweet peppers, and onions served with Dublin Bay prawns

tarte aux sardines fresh sardines baked on puff pastry served with a seasoned tomato purée

terrine de foie gras aux purée de prunes terrine of fattened duck liver and veal aspic served with prune purée

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Chef Médigue served his gaspacho preparation with two langoustine tails. These are hard to get where I live so I’ve substituted a simple decoration of sweet red and green pepper confetti and fine shreds of cucumber and chives.

Other toppings can be used. At one restaurant in Paris they served their gaspacho with a couple of anchovies and pickled green beans and a few drops of flavored oil.

The purée can be made a day in advance. Add the mayonnaise mixture and emulsify with the immersion blender just before serving.

Gaspacho

- 31/2 ounces pain de mie, crust removed, coarsely dice

- 21/4 pounds plum tomatoes, peeled, seeded, coarsely diced, juice reserved (yielding about 11/2 pounds)

- 21/2 ounces (about 1/2 medium) red onion, coarsely dice

- 2 cloves garlic

- 4 ounces (about 1 medium) red pepper, coarsely diced

- 41/2 ounces (about 1/2 medium) English cucumber

- 8 medium leaves basil

- 1 teaspoon ground cumin, infused in 1 tablespoon boiling water for 10 minutes

- 1 tablespoon salt

- 1 teaspoon ground white pepper

- 2 drops Louisiana hot sauce

- 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar

- 1 egg yolk

- 1/4 cup olive oil

- Combine bread cubes and tomato juice. Moisten with additional cold water if bread seems too dry.

- Combine bread, tomatoes, onion, garlic, red pepper, cucumber, basil, cumin water, salt, white pepper, hot sauce, and vinegar in a bowl. Purée, in batches, in a blender at the highest speed.

- Prepare an aïoli out of the egg yolk and olive oil. Add tomato mixture and stir to combine. Set aside in refrigerator for at least 2 hours.

- Just before serving, emulsify further with an immersion blender and divide among serving plates.

Yield: 4 servings.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Frédéric Médigue, chef and owner of the Château, shown with Patti Ravenscroft, organizer and leader of our week in Amondans

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved

At the end of each meal, a tray of small sweets, les mignardises, was presented to the table. This is in addition to dessert! Chef Frédéric Médigue’s offering included miniature eclairs, miniature profiteroles, madeleines, macaroons, miniature lemon tarts, and candied orange peel. A better plate of fat pills can not be found anywhere!

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

l’amuse-bouche: brochettes de caille a starter of grilled quail with diced cornichons, pickled carrot and sauces of mustard and reduced balsamic vinegar

velouté de choux-fleurs aux girolles à l’huile de noisettes a thick cauliflower soup topped with girolle mushrooms and hazelnut oil

escargots de Bourgogne en verdure, crème de raifort aux radis roses snails from Burgundy wrapped in green chard served with a sauce of horseradish and red radishes

salmis de pigeon fermier, essence de Banyuls a stew of boneless squab served with a sauce of wine from Banyuls

morbier rôti, vinaigrette de betterave roasted morbier (cheese) served with diced beets in a vinaigrette

les pamplemousses roses à la liqueur de gentiane et zestes confits, crème de noix de coco givrée les mignardises red grapefruit in a sauce of gentiane liquor and stewed grapefruit skin, topped with a custard of coconut milk covered with sugar crystals accompanied by a plate of small cookies (not shown)

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Mungo Park, the restaurant in Besançon, was named after Mungo Park (1771-1806), a Scottish explorer. He mapped large areas of the interior of Africa for the first time, determined the course of the Niger and died trying to find its source.

The following is excerpted from an Amazon.com book review for Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa by Mungo Park and James Rennell.

Mungo Park was the first European to visit the Niger River basin in 1796. He resolved, once and for all, a debate that had European cartographers and geographers confused for centuries.

His initial journey (1795-1797) was a tale of tremendous personal hardship and suffering, but triumph in the end. After returning to Scotland in 1798, he became acquainted with Sir Walter Scott. They became close friends, and it was Sir Walter Scott who convinced him to return to Africa to uncover the secret of the mouth of the Niger River.

In 1805 he convinced the British government, in the middle of a war against Napoleon, to send another expedition to seek out the mouth of the Niger. With 100 officers and men he set out, retracing his earlier steps. The journey was filled with personal tragedy and heroism. After arriving on the Niger, he built a boat, named the Joliba, and traveled down the river. During the course of his journey he met and traded with the many kingdoms that lined the river. However, he also incurred the wrath of many local kings and chiefs who believed that he was cheating them.

Near the town of Bussa (now covered by a huge dam), Mungo Park met his unexpected end. For many years it has been assumed that he was attacked by hostile natives seeking to rob him. In fact it may have been due to the fact that he just failed to navigate the river.

Excerpted from the text of the book, originally published in 1797:

…they supply the inhabitants of the maritime districts with native iron, sweet-smelling gums, frankincense, and a commodity called shea-toulou, which, literally translated, signifies tree-butter. This commodity is extracted from the kernel of a nut by boiling the nut in water…

The extract has the consistency and appearance of butter ; and is an admirable substitute for it. It is an important staple in the food of the natives and therefore the demand for it is great.…

The people were everywhere employed in collecting the fruit of the shea trees. These trees grow in great abundance all over this part of Bambarra. They are not planted by the natives, but are found growing naturally in the woods ; and in clearing wood land for cultivation, every tree is cut down but the shea.

The tree itself very much resembles the American oak ; and the fruit, from the kernel of which, being first dried in the sun, the butter is prepared by boiling the kernel in water, has somewhat the appearance of a Spanish olive.

The kernel is enveloped in a sweet pulp, under a thin green rind.

The butter produced from it, besides the advantage of its keeping the whole year without salt, is whiter, firmer, and, to my palate, of a richer flavor than the best butter I ever tasted made from cow’s milk. The growth and preparation of this commodity seem to be among the first object of African industry in Bambarra and the neighboring states ; and it constitutes a main article of their inland commerce.…

In a little time the “Douty” sent for me, and permitted me to sleep in a large balloon, in one corner of which was constructed a kiln for drying the fruit of the shea trees ; it contained about half a cart-load of fruit, under which was kept up a clear wood fire. I was informed that in three days the fruit would be ready for pounding and boiling, and that the butter thus manufactured is preferable to that which is prepared from fruit dried in the sun…

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The village of Ornans is mostly known as the birthplace (1819) of the painter Gustave Courbet. Pierre Vernier, inventor of the vernier caliper, was also born here. The written history of the town dates back to 1244.

Today the village is the “capital” of the Loue valley. The stretch of river flowing between the double row of old houses on piles is one of the prettiest scenes of the Jura.

If you’re walking around town and become hungry, you can get a good pizza at Le Chavot in Ornans and eat at a table overlooking the river.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Located at the entrance of the main shopping street of Besançon (population 115,000) is a patisserie by the name of Baud. Baud is a member of the prestigious Relais Desserts International — an exclusive trade organization.

The somewhat ordinary looking sales area and restaurant hides the fact that here one can find world-class pastries, chocolates, and ice cream at Baud. (The free samples were mighty tasty!)

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

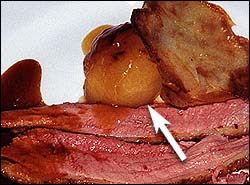

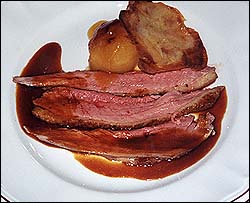

Chef Médigue served a caramelized peach with a roasted duck breast one evening. The arrow above identifies the peach. The mass to the right is a simple potato galette. I later asked him how the peach was prepared. The following is my interpretation of his description, as tested in my kitchen.

Pêche Confit

- 1/4 cup butter

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 2 small peaches, peeled

- Preheat oven to 425 °F.

- Place butter and sugar in a small ovenproof sauce pan over medium heat. When butter and sugar are melted, add peaches, and place in oven.

- Bake for about an hour until caramelized and soft. Stir every 10 minutes.

- Let sit for 10 minutes or so before serving to cool slightly.

Yield: 2 servings.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The following are examples of some of the plats (main courses) served by Chef Médigue during the week at the Château d’Amondans…

merlan braisé au petit lait, gratin de pain à la sauge whiting braised in milk with a topping of bread and sage

selle d'agneau de sisteron rôtie aux tomates, aubergines et courgettes roasted saddle of lamb with baked tomatoes, eggplant, and zucchini

canard rôti aux pêches confites roast duck breast served with a baked peach and a potato “galette”

canard rôti part dieu roast duck legs

risotto de saint pierre au cèpes rice with John Dory served with mushrooms and herb sauce

poulet aux vin jeune traditional Jura-style roast chicken with a sauce made from straw wine and served with morels and rice

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

In the 1999 Michelin Red Guide there were 479 restaurants awarded at least one star. This represents less than one percent of all the restaurants in France. The Guide states: “Certain establishments deserve to be brought to your attention for the particularly fine quality of their cooking. Michelin stars are awarded for the standard of meals served.”

There are 21 three-star restaurants: “Exceptional cuisine, worth a journey. One always eats here extremely well, sometimes superbly. Fine wines, faultless service, elegant surroundings. One will pay accordingly!”

There are 74 two-star restaurants: “Excellent cooking, worth a detour. Specialties and wines of first class quality, This will be reflected in the price.”

Finally, there are 402 one-star restaurants: “A very good restaurant in its category. The star indicates a good place to stop on your journey.” Les Château d’Amondans is one of these one-star restaurants.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

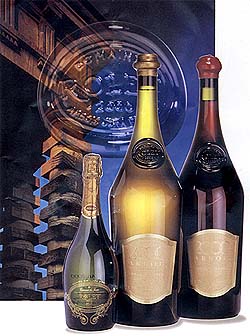

Domaine Rolet Père et Fils

With its 60 hectares distributed over the best hills of the Arbois and Cotes du Jura AOC vineyards, the Rolet Estate is the second largest wine-growing concern in the Jura.

36 hectares of Arbois AOC on the Arbois and Montigny communes where Poulsard red vine varieties on blue and red marls are dominant, Trousseau on the thick gravel soils, especially warm ground, 35 hectares where young plants are placed side by side with the first plantations of the Estate, nearly fifty years of age in the famous places of “Gaillard, Chagnon, l’Euvrin, Vauxelles, Chateau-Gimont, le Moulin” in the Montigny commune and “Montesserin” in Arbois.

24 hectares in Cotes du Jura AOC where white vine varieties are dominant, Chardonnay and Savagnin, on very specific native soils with liassic gray marls of Voiteur and to a lesser extent, Poulsard and Pinot Noir on the steep foot-hills of the Grandvaux in Passenans.

The complexity of such a diversity of vine varieties is the result of our permanent concern for finding the best combination of soils, under-soils and vine varieties.

A family: An Estate which reflects the image of an ever-changing Jura and family enterprise, this Estate was created in the early 40’s by Desire Rolet. To-day, his children have taken over and share the various responsibilities of the management of the Estate, Bernard and Guy take care of the vines and vinification; Pierre and Eliane are in charge of marketing, each one of them working with a view to the final objective of a winegrower: the passion of obtaining, depending on the vintage, the quintessence of the grape knowing that wine starts being made in the vineyard.

With modern air-conditioned wine-making plant where stainless steel vats, new barrels and oak casks are next to each other, from grape picking to bottling, we apply all of our know-how to the making of highly renowned vintages.

Vine varieties on the Estate: Chardonnay: 34%; Savagnin: 21%; Poulsard: 21%; Trousseau: 10%; Pinot Noir: 13%.

The deliberate and patiently carried out selection of balanced vine variety stock on the most favorable soils in Arbois as well as Cotes du Jura AOC enables us to offer a complete range of the wealth of our native soils, pioneers in the Jura of typical red and white wines produced from a single vine variety which complement the traditional vintages.

White Arbois Chardonnay: native of Burgundy, it found in the Jura another friendly soil since the XIVth Century, classical vintage of great white wines; its aging in new casks gives it lingering fragrance and vanilla aroma. Lasting from 10 to 15 years, with age it acquires nobleness and character. Served cool, it admirably accompanies entrees, seafood and fish dishes.

Cotes du Jura Chardonnay: aged for 21 months in casks having contained wine in order to thoroughly enhance the firm personality of the Cotes du Jura, it is a Chardonnay with a very personal native tang of flint stone and roasted almonds. Served at cellar temperature, it is best with pates, hot fish dishes and smoked cold cuts. It can be kept from 10 to 15 years.

Arbois and Cotes du Jura Chardonnay-Savagnin: after 30 months of aging in casks, a happy mixture of the fullness and subtlety of Chardonnay and of the complexity of the Savagnin which gives it body and its so characteristic walnut aromas; very typical wines to be served at 14 °C approximately and uncorked well in advance, they go marvelously well with seasoned dishes, such as fish, sweetbreads and poultry in cream sauces, seafood croustade and cheeses. It can be kept for 12 years and more.

Arbois Rose: the only Rose wine to be obtained following a ten-day maceration, mainly of the Poulsard vintage. Fruity wine, it very rapidly acquires during aging an onion-skin bronze color. Served cool, it goes well with cold cuts, grilled meats and poultry dishes. It keeps for 7 to 10 years.

Arbois Red Tradition: vintage traditionally made of three vine varieties: Poulsard, Pinot and Trousseau. After aging for 18 months in casks before being bottled, it requires 2 to 3 years in a cellar to reach its equilibrium, light red, served at cellar temperature, it may be drunk from beginning to end of any meal. It keeps for 8 to 12 years.

Arbois Poulsard “Old Vineyards”: a choice of grapes from 20-year and more old vineyards, a light flavored and charming red wine with small red berry aromas. Rich when young, after aging it develops a cooked prune aroma. Served between 13 and 15 °C, it goes well with pates, white meats, leg of lamb and roasts. It keeps for 8 to 12 years.

Arbois Trousseau: the smallest red wine vintage of the Jura which is at its best on the native hills of Montigny, a very long keeping wine. Following aging for 18 months to 2 years in casks, it develops complex aromas: leather and meaty flavor and after being bottled for several years, it is then fully developed and mushroom and forest aromas appear. It will go well with prepared meats, game, venison and cheeses. It should be kept for a while at room temperature. It keeps for 15 years and more.

Arbois Pinot: a good Jura version of this renowned vintage, vinous red with specific aromas acquired during aging in new casks, well known to wine tasters. Its mellowness and bouquet are appreciated by and large. It goes well with red meats and cheeses. Served between 15 and 16 °C. It keeps for 8 to 15 years.

Arbois Yellow Wine: the King of wines and Wine of Kings; exclusively produced from the Savagnin vine variety. To reach its fullness which challenges the laws of analogy, it requires six years without topping up during which it acquires its unequalled walnut flavor. Bottled in a Clavelin (specially shaped bottle), it is a highly gastronomic wine which goes marvelously well with the dishes for the preparation of which it has been used: chicken with Yellow wine sauce and morels, veal meat and fish dishes with cream sauce, Franche-Comté cheeses. Served at 15 °C, always uncorked in advance. It keeps for 100 years and more.

Arbois Straw Wine: selected crop from the nicest grape clusters, in general from Chardonnay and Savagnin, sometimes Poulsard, which are put to dry for 2 to 3 months on trays. The raisined grapes give a very small quantity of slightly liquorous wine with a 15 to 17% of alcohol, which is traditionally conditioned in half-bottles. It is drunk cool and goes well with foie gras, aperitifs and desserts. It keeps for 30 years and more.

White and Rose Sparkling Wines: produced in the Jura since the XVIIIth Century according to the Champagne method, called to-day “traditional method”. The whites are made with Chardonnay and the Roses with Poulsard. As time goes by, they have become very famous. Wines for celebrations, they will be served chilled as aperitif or at the end of a meal.

Macvin: Regional wine-grower aperitif; liquorous wine produced after adding old Jura brandy to grape juice. Its specific character has just been recognized by the granting of the guaranteed vintage label. Served iced for aperitif. It goes very well with melons and ice-creams and will be very much appreciated by ladies as a liquor.

Old Brandy and Old Fine (High Quality Brandy): the Brandy is obtained by distillation of destemmed grape brandy and the Fine by wine distillation. They are among the best French alcohols. They are aged in oak casks. Powerful and aromatic, they all have the personality of the native soil of the region. Served after remaining for a while at room temperature, they are very much appreciated.

Excepted from literature provided by Domaine Rolet Pére et Fils.

©1999, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.