For me, one of the most frustrating times is when I give someone a recipe and the first thing they ask me to do is to convert all the measurements. They’re not asking me to convert tablespoons to teaspoons, but some weight measurement to a volumetric measurement. For example, how many cups of flour should be used when the recipe calls for 750 grams? Or, how many tablespoons of salt is 20 grams?

In cooking, various measurements are used depending on need. These include volume, length, weight, temperature, and descriptive measurements. Then, there is added confusion when Americans use English units of measure while most of the rest of the world uses the metric system.

Measuring by weight instead of volume: American home cooks have a tradition of using volumetric measures for dry ingredients. Home recipes will list ingredients such as flour or sugar by volume, e.g., cups or tablespoons, whereas commercial recipes will measure these ingredients by weight. In France, weight is generally used for larger quantities. Volume is used for a few tablespoons or less, especially if the amount is not critical. The problem with measuring dry ingredients, such as flour, by volume lies in the fact that the type of flour, humidity, and whether or not it is sifted can affect the amount of flour actually used. Whether sifted or not, a pound of flour is always a pound of flour.

Lack of precision in ingredient specifications can also lead to differences when using volumetric measures. Using salt as an example, I measured two tablespoons, five times, of two different types of salt commonly used in French cooking, fin sel (fine salt) and gros sel (coarse salt). For each measure, a two tablespoon measuring cup was dipped into a larger container of salt to produce an amount greater than two tablespoons. A small spatula was then used to level the top of the salt. In the case of the gros sel, the salt was also packed into the measure slightly to make sure there were no air pockets. The five gros sel measurements ranged from 21 to 24 grams (g). All of the fin sel measurements weighed 25 g. On average, two tablespoons of fin sel weighed 12% more than the gros sel. Additionally, because of the structure of gros sel and its inherent moisture, the measurements had a fair amount of imprecision. If a recipe calls for 20 g of salt, it’s possible to measure 20 g of salt without the imprecision induced by a measuring spoon.

Irregularly shaped dry objects like dried fruit and nuts are also difficult to measure precisely with volumetric measures. I have seen too many recipes call for a cup of walnuts without specifying whether they were coarsely chopped, pieces, halves, or whatever. By weight, no matter which type of nut was measured, the result would be the same amount of nut meat, whereas measuring with a measuring cup, varying results would be produced. Simply weighing ingredients increases the accuracy of the measurement process compared to using volumetric measures, if good weighing technique is used.

Choosing the right scale: There are a number of types of scales currently available for kitchen use. Electronic scales are the easiest to use and the most accurate, assuming the user remembers to zero the scale before use. Spring scales are less expensive than electronic scales, but lack precision when measuring small quantities. Balances are traditionally the most accurate kitchen scale, but these are usually only found in commercial kitchens, and even less and less there.

When choosing a scale suitable for home cooking, be sure to get one with a resolution of 1 g (or 0.125 oz). There are scales with resolutions of 2 g (0.25 oz) or greater, but this resolution is not good enough for small portions of dry ingredients. The maximum capacity should be at least 2000 g (4 pounds). There should also be a “tare” feature so you can zero out the weight of the bowl being used to hold the item being measured. The scale I use measures in either English or metric units to a precision of 1 g or 0.1 oz. It has proved to be invaluable on many occasions, and after my knives, is probably the most important device I use in the kitchen, and I use it daily.

Grams are more convenient to use for most weight measurements because in the quantities used for cooking, fractions are not required. With the English system, fractions of ounces would be required to equal the precision obtainable with whole grams.

Although less common, it is not unheard of to measure liquid ingredients by weight instead of volume. Unfortunately, the French haven’t settled on a single unit for fractions of a liter (l). Some recipes will be in deciliters (dl) or 0.1 l. Others will be in centiliters (cl) or 0.01 l, while some are even in milliliters (ml), or 0.001 l. By design, one milliliter (ml) of water weighs 1 g. If you are already using a scale to measure the dry ingredients and the recipe calls for 250 ml of stock, this will weigh very close to 250 g and can be measured quickly on the scale without getting a measuring cup dirty.

In America, where liquid measurements may be in cups, pints, quarts, etc., or fractions thereof, the conversion to weight is more difficult. The old saying, “A pint is a pound the world ’round,” is close to the truth, but the error is about half an ounce (or one part in 32). But using a pint to measure a pound is often close enough.

Two volumetric measures that French and American recipes have in common are the tablespoon, cuillere à soupe, and the teaspoon, cuillere à café. In France, a tablespoon is equal to 15 ml, and a teaspoon, to 5 ml. In the United States, these measures are slightly smaller — about 1%. In older French cook books, sometimes a verre, a glass, or tasse, a cup, is found as a unit of measure. I have not found a standard definition for either of these measures. Furthermore, for Americans, the use of milliliters is simple because standard U.S. measuring cups all have fractions of cups, ounces, and milliliter graduations.

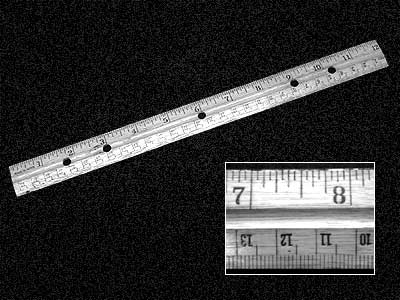

The long and the short of measuring: In measurements of length, America and France are also in disagreement. Americans use feet and inches. The French use the metric system — millimeters, centimeters, and meters. Once again, with the metric system, it is possible to easily measure most things in the kitchen without needing to use fractions since the smallest common unit, the millimeter (mm), is approximately equal to 1/25 of an inch. It is rare that a recipe specifies a measurement smaller than a millimeter. With the English system, fractions of inches are used, and abused, all the time. Most rulers in America come with both English and metric units, and every kitchen should have at least one ruler in its armamentarium.

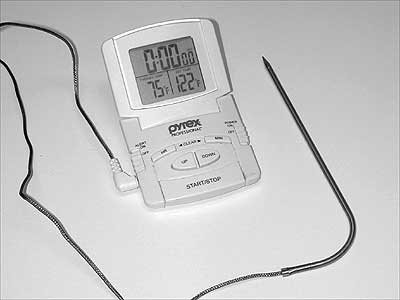

The hot and the cold of measuring: Even with measurements of temperature, most digital thermometers read in either centigrade or Fahrenheit. Although I find centigrade measurements more convenient, it is harder to make a case for centigrade measurements over Fahrenheit. This is especially true since ovens in the United States are usually only able to be set in Fahrenheit units. In France, some ovens are set in centigrade units, but others use “thermostat” settings of 1 to 10.

Tell me what you really mean: The least standardized form of measurements is descriptive measures. Some of these measures, such as dollop, handful, and spoonful, have thankfully gone the way of the buggy whip. Others are firmly with us. Adjectives such as thinly, finely, and coarsely combined with instructions like mince, slice, dice, and chop are found in many recipes, including my own. Each assumes the reader possesses knowledge that only can be gained by first making the dish described by the recipe! If these descriptive measurements were combined with standardized length measurements, instructions would be clearer. For example, “1 mm thick slices.” There are cases, however, where adding a length measure is inappropriate. If a recipe calls for finely minced, I assume the instruction means for the cook to mince the ingredient as finely as they can.

Another problem brought about by descriptive measures is cultural. A large, medium, or small apple, onion, or tomato may not mean the same thing to all readers. It is much better to apply a description of weight to ingredient specifications like these.

Even the pros do it: Because of my background, I may emphasize precision a bit more than necessary, but I bristle when someone says to me that professional chefs don’t measure. In every kitchen I’ve been in I’ve seen chefs measuring everything they do. Sometimes it may not appear that they are measuring, but they use a combination of their eyes and experience to measure. If you ask them how much of an ingredient they just added to a pot, they can usually tell you a quantity. Sometimes the amount is based on taste, another means of measuring. Portion control is very important in a commercial kitchen, so measuring is done all the time and at all stages of preparation. If measuring wasn’t taking place, the chef wouldn’t know how much raw ingredients to order for a planned number of portions. This is especially important when special dishes are prepared for banquets — the chef neither wants material left over, nor to finish the meal service one portion short!

Keeping it clear in recipes: When testing and transcribing recipes, I have adopted a pattern that may not appear obvious to the reader. First of all, I attempt to work with the units of measure as they appeared in the original recipe. Metric units remain metric, except I have standardized on milliliters for volume and grams for weight. Thus centiliters and deciliters are converted to milliliters and kilograms are converted to grams. I have done this for two reasons. First, using a smaller variety of units is less confusing. Second, my measuring equipment favors grams and milliliters. English units usually remain unchanged. When a measure is really intended to indicate an amount purchased rather than an amount to be measured in the kitchen, I will usually (but not consistently) state the amount in the form that it is purchased in at my local market, for example, 1 pound asparagus or 1/2 pound onions. In some cases, when small amounts of ingredients are specified as tablespoons or fractions of tablespoons, I will convert these measurements to grams to obtain consistency each time the recipe is prepared. If the amount is non-critical, I will usually leave it unmodified.

By their very nature, recipes tend to be imprecise. In most cases, this is not a problem because the experience of the cook will overcome the lack of precision. In some cases however, the lack of precision leads to the evolution of a different dish than originally intended by the recipe author, or the lack of precision leads to disappointment and another addition to the trash bin. I hope my efforts at the art of recipe writing do not contribute to your local landfill.

©2000, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.