What would be the first thing to come to mind if you were invited to dine on pigeon? Would you run the other direction? Would you question the sanity of the person offering the invitation?

Pigeons are not held in high esteem by the average person. These are the filthy birds that seem to litter public spaces the world over. (These noisy birds sit outside my window and wake me in the morning or disturb me as I try to work.) They formerly served a useful purpose in times of war, carrying messages, but they are now left to begging on the street for food like other veterans damaged by the experience.

In English, “pigeon” often denotes a negative context. A pigeon is an easy mark, a dupe. A stool-pigeon betrays confidences. Walking pigeon-toed sends us to a podiatrist. And clay pigeons are too stupid to hide when necessary!

When we do consider eating these “flying-rats,” we call them squabs. And this is not a new practice, the Oxford English Dictionary cites a 1694 reference referring to the raising of squobbs for food. (There seems to be a consensus that the word squab is of Scandinavian origin, probably Swedish, where the meaning referred to anything that was soft and thick.) Although we eat squabs — don’t call them pigeons — a squab can also be a short, fat person or a couch. Don’t squabble with me, it says so in the dictionary.

As the poet Ogden Nash once quipped:

Toward a better world I contribute my modest smidgin;

I eat the squab, lest it become a pigeon.

Technically, a squab is a young pigeon — about four weeks old. (The French word for a young pigeon, or squab, is pigeonneau. The French word for a pigeon is pigeon.)

The squabs available in the market are farm raised. I have never tasted wild pigeon, but I assume it is like other fowl in that the wild ones tend to be gamier and tougher than their farm-raised cousins. (Plus there's never any buckshot in the farm-raised birds.) Although there is some meat on the legs and wings, most of the meat on a squab is breast meat. When the breast meat is cooked medium-rare, it is both moist and succulent. Because of the lack of fat, squab will be chewy if even slightly overcooked. Like duck, the meat is layered not marbled.

The concept for this recipe originated with Chef François Kiener at Auberge de Schœnenburg in Riquewihr, France. On a recent visit, I had the pleasure to participate in the boning and skewering of a bunch of squabs. (What is the right name for a group of young pigeons? A clique?) At the end of my visit I had the pleasure of eating the completed dish in the main dining room of the Auberge.

Chef Kiener never disclosed the actual sauce ingredients he was using — I never asked — so the sauce provided in the recipe is a traditional, simple sauce made from the bones of the bird. Chef Kiener served the squab with cooked vegetables as described in the recipe. Because of the small quantity of each item used in a single serving, this can be an inconvenient recipe for just a few people. At the Auberge, twenty servings were prepared at once. A simple vegetable accompaniment, such as sautéd spinach or chard, would be very nice with this dish.

The following recipe serves two.

freshly ground black pepper

Preheat oven to 205 °C (400 °F). Melt the butter in a frying pan over high heat. Season

pigeon halves with salt and pepper. Brown one side. Turn the halves over, and place the pan in the oven. Cook for 7 minutes.

Place the baked pigeon halves on a plate, tent with foil, and set aside to rest for five minutes. While the pigeon is resting, continue to reduce the

sauce until thickened. Taste the sauce and season with salt, as required. Also, place the serving plates with the

vegetables in the oven for a couple of minutes until the vegetables are reheated.

When the meat has rested, slice each half on the bias in four places. Arrange the pigeon slices on the serving plates. Top with the reduced sauce.

2, about 500 grams (1 pound) each

young pigeons (squabs)

1/8 teaspoon

ground star anise

1/4 teaspoon

ground coriander

1/8 teaspoon

ground cloves

1/4 teaspoon

ground nutmeg

1/8 teaspoon

ground white pepper

It’s best to start with a pigeon that still has its head and both feet attached, but not for the thrill of removing these anatomical parts. The bones of discarded appendages of the pigeon will be used for making the stock for the sauce, so the feet and neck are needed. Also, by having these items still attached, it is possible to ensure that they are removed carefully so the finished, boned morsels assemble properly. Remove the liver, heart, and gizzard from the carcass, and set aside. Cut the head off the neck and discard.

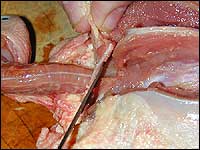

Start boning the pigeon by cutting through the breast skin directly above the breastbone. With the knife edge scraping the bone, remove the breast meat from the bone. Try not to cut into the meat.

Continue separating the breast from the carcass until the meat is totally free from the bone. Next separate the breast meat from the other side of the breastbone in the same manner.

[Optional] Remove the wishbone (clavicles) at the neck end of the breastbone. Reserve the wishbone along with the other bones removed from the pigeon.

Remove the small tenderloins found underneath each breast fillet. Carefully remove the tendon from each of the tenderloins by scraping along the tendon with the knife while holding the tendon with a fingertip. Set aside the tenderloins until needed.

Flip the pigeon over and cut through the back skin from neck to tail. Cut off the tail and reserve with the bones.

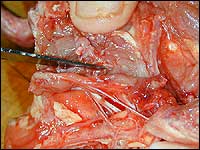

Separate the upper wing bone on one side from the carcass. Be careful to insert the knife between the cartilage at the end of each bone, cutting through the tendons that hold the two bones together. Repeat the process for the wing bone on the other side.

Using your fingers to find where the thigh bone attaches to the carcass, use the tip of a knife to separate the two bones similar to the way the wing bones were separated. Do this on both sides of the carcass. It should now be possible to remove the meat completely from the carcass resulting in two halves, each with one leg, one breast, and one wing. Use the edge of the knife to scrape along the carcass at any place the meat is still attached to the carcass. Be careful not to cut through the skin. Chop the carcass bones into small pieces and set aside with the other bones.

Remove the feet from the legs and set aside with the bones. Cut through the wing between the joints of the upper and lower bones. Set the wing tips aside with the bones.

Purée the livers by forcing them through a fine sieve. Set the purée aside. Discard the veins and other tissue that don’t pass through the sieve.

Lay each of the halves on a board, skin side down. Make a small pocket between the breast meat and the skin. Spread a teaspoon or two of puréed liver in the opening. “Seal” the opening with one of the reserved tenderloins. Repeat for the other breasts.

Season the meat side of the halves with some of the spice mixture.

Fold each half over until the cut edges meet. It may be necessary to trim off excess skin remaining near the neck. Using a small metal or wooden skewer and working from an end, “weave” the skin flaps together. Pierce the two layers with the skewer from one side. Push the tip through about a centimeter, bring the tip back over the edges, and push the tip through the skin again. Continue until the center is reached. Start again from the opposite end with another skewer.

Straighten the skin out along the skewers. Lay the halves out flat on a plate. Cover with plastic film and refrigerate until needed.

1-1/2 tablespoons

dehydrated chicken stock

3 tablespoons

melted butter

1/4 teaspoon

dehydrated chicken stock

salt and freshly ground pepper

4 to 6

young snow peas, stringed

4 to 6

French green beans, trimmed

2

cabbage leaves, trimmed

2 to 4 thin

asparagus stalks, trimmed

2

spring onion bulbs, halved

Select and prepare, as described above, a selection of vegetables.

Bring the blanching liquid to a boil in a saucepan. Blanch each of the vegetables in separate batches until almost cooked. Drain each batch and mix with some of the seasoning mixture. Set each vegetable aside separately.

For serving, carefully unwrap the vegetables and arrange on ovenproof serving plates. Reheat per the main recipe.

bones from 2 young pigeons (squabs)

1

plum tomato, seeded and chopped

1 small

carrot, peeled and chopped

1/2 stalk

celery, peeled and chopped

Preheat oven to 260 °C (500 °F). Scatter the reserved bones in a baking dish and bake for 15 minutes.

Scatter the vegetables over the bones and bake for an additional 15 minutes.

Transfer the cooked bones and vegetables to a saucepan. Add some water to the roasting pan and deglaze over heat. When all the caramelized partials are loose, transfer them along with the water to the saucepan.

Add sufficient water to the saucepan to cover the bones plus another 50 percent. Bring the water to a boil. Reduce heat to simmer. Simmer the contents for about 2 hours until the liquid is reduced by half. Skim any scum that forms on the surface. When reduced, strain the stock through a strainer and then through a chinois. Check the volume of the stock. If it is greater than about 200 milliliters, reduce further. Refrigerate strained stock until needed. Remove and discard any fat that congeals during cooling.

©2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.