October 28, 2013

Amuse-Bouche

quenelles de foie

(liver dumplings)

Berta Guggenheimer was born in Munich on March 4, 1887. In 1904, at the age of 17, she was sent to Vienna for a year to learn how to be a “proper young women.” While there, she recorded what she learned in a series of bound notebooks. Some entries were just private thoughts and a few were pen and ink drawings. Two volumes were mostly recipes. Berta was my mother’s mother. I always knew her as O’ma. When my grandmother died in 1963, those books went to my mother, and when she died in 1981, they came into my possession. I’ll return to them in a few paragraphs.

On August 16, 1910, Berta married an ophthalmologist by the name of Simon Koschland. They settled into a house in Munich, and it was there my mother, born in 1914, and her brother, born in 1911, were raised. During the First World War, my grandfather, who I always knew as O’pa, served in the German army as a medical officer. His discharge papers list the exact enlistment dates and the six specific military units he was assigned to during four years he spent in the army. The papers do not indicate that, while in the army, O’pa contracted the tuberculosis that afflicted him on-and-off the remainder of his life.

My mother left Germany on March 23, 1934. Her brother accompanied her from Munich to Rotterdam, where the still 19-year-old x-ray technician boarded a British freighter bound for San Francisco. Shortly after May 13th, the now 20-year-old woman, who for the remainder of her life swore like a British sailor, arrived at her aunt’s house in Alameda, California, a short ferry ride across the bay from San Francisco.

My uncle left Germany a short while later, and eventually landed in Palestine. There he would marry and have a daughter. In 1947, the three of them immigrated to the United States. The daughter is my only first cousin.

For reasons not clear to me, my grandparents remained in Germany until 1939 when they were able to emigrate to London as refugees. My father sponsored them into the United States in 1940. Upon arrival, their names were simplified a bit and my grandmother became Bertha Koshland.

I always remember O’ma as a gentle women, but also one who was often verbally abused by her husband. I couldn’t tell what he was saying, they always spoke German to each other, but I could surmise the message from the tone and her response. My grandfather was a bitter man. Having arrived in the United States at the age of 61, he wasn’t allowed to practice medicine because he lacked a California medical license. He spent the rest of his working life sweeping out the back of a drapery shop in San Francisco.

I remember very little about O’ma’s cooking. Their apartment at the corner of Turk and Arguello in San Francisco was small. It was filled with objects they brought—I don’t know how—from Germany. We rarely, no more than once or twice, had family meals there. My mother, who seemed to have an off-again-on-again relationship with her parents, always described her mother’s cooking with warm memories and pleasant thoughts. And she coveted O’ma’s handwritten recipe books.

One dish that my mother prepared during my teenage years that she ascribed to her mother was leberspätzlesuppe. It was a clear broth with tiny liver “dumplings”—I thought at first they were worms and always call them that—resting on the bottom of the soup bowl. By the time I got around to asking her for the recipe, years after my grandmother had died and she had inherited the recipe books, she was already ill with cancer and no longer remembered how she prepared the dish. When I came into possession of the recipe books, I scoured them for the leberspätzlesuppe recipe but it wasn’t there. I became resolved that the dish was lost to me forever. That was over thirty years ago.

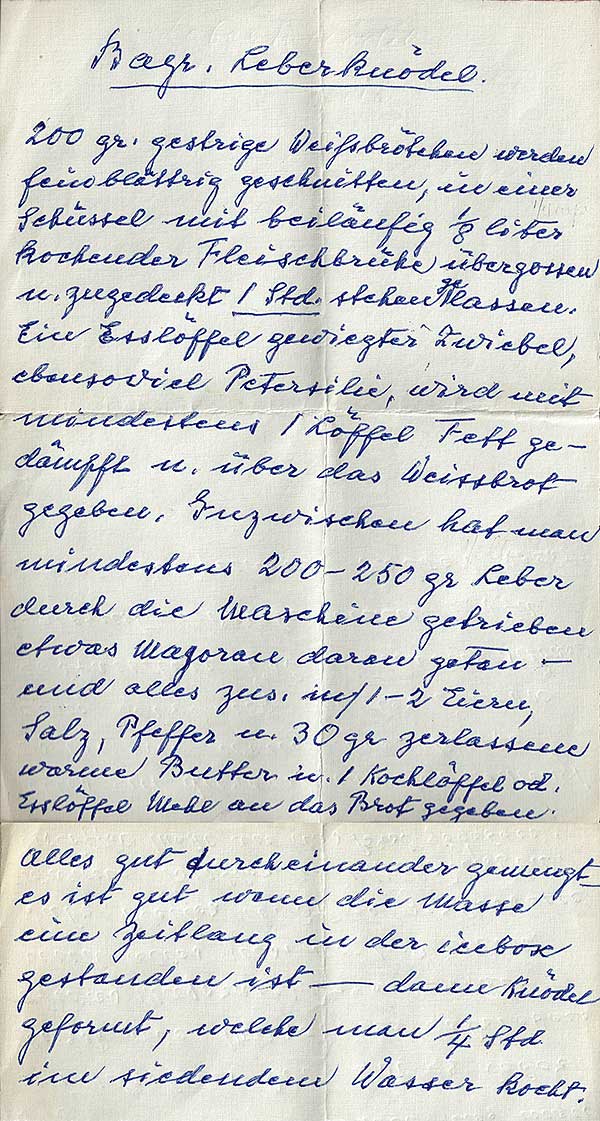

Late one night last July, I decided to look through my mothers old, metal recipe box for a particular fruit tart she used to make. I had looked in the box in the past for specific recipes, but this was the first time I systematically went through it from start to finish. Some of the three-by-five-inch recipe cards have a faded newspaper clipping taped to them. There’s the occasional card handwritten by my mother or one of her friends. There’s even a few that are clumsily typewritten by my mother. Interspersed are folded pieces of paper with various bits of information written on them. This night, I unfolded a piece of buff-colored paper to find German script in what I recognized as O’ma’s hand.

From the title at the top of the page I could see the recipe was not for leberspätzlesuppe but it was close. The recipe was for leberknödel. As I tried to understand the recipe instructions I wondered: Had my mother adapted this recipe for her soup? I could make out some of the recipe, but not enough to truly understand it. The recipe was undated, but I assume it was written during the late 1950s or early 1960s.

I scanned the recipe and sent it off to a number of people I knew could translate German recipes. In the end, Barbara Treutlein, an associate of my wife’s at The Quake Lab (Stanford University) sent me a reasonable translation.

Bavarian Leberknödel (“liver dumplings”): Cut 200 g of white bread rolls from the previous day into fine slices and in a large bowl, pour 1⁄8 liter of boiled meat broth over the bread pieces. Incubate for 1 hour without cover. Shortly sauté 1 tbsp of finely minced onion and 1 tbsp of minced parsley with at least 1 tbsp of fat and add to white bread. In the meantime, grind at least 200-250 g of liver through the machine, add a bit of marjoram and add everything together with 1-2 eggs, salt, pepper, 30 g of melted butter and 1 tbsp or cooking spoon of flour to the bread mix. Mingle everything well — it is good when the mixture rests for some time in the icebox. Form dumplings (roll balls with both hands) and cook for 1⁄4 hour in scalding water.

I could easily see how this mixture could be lightened a bit with a little egg and forced though my grandmother’s old spätzle maker into broth. When I went to the kitchen to give the recipe a try, I found myself making miniature leberknödel instead of the spätzle. The ingredient quantities I tried produced 24 little leberknödel. Oh well.

70 g (2-1⁄2 oz)

dry bread crumbs

1 T

finely diced onion sweat in 1 T duck fat until translucent, chilled

140 g (5 oz)

ground beef liver

1⁄2 t

dried marjoram

1 extra-large (50 g, 1-3⁄4 oz)

egg, beaten

30 g (2 T)

melted butter

fine salt, to taste

finely ground black pepper, to taste

1. Mix everything together, and set in your refrigerator to chill for a couple of hours.

2. Using a 2.5 cm (1-in) wide ice cream scoop to portion the dough, form it into balls with your hands.

3. Bring a saucepan of water to simmer over the medium heat. Keep the water at 74 to 82°C (165 to 180 °F) during the cooking. Add the leberknödel to the water, and stir once or twice gently. When they float, set your timer for 1 minute. Finish cooking.

4. Remove the leberknödel to an ice-water bath, and chill them for 5 minutes. Drain well, and finish chilling in your refrigerator. Use the same day or so, or freeze.

5. To serve, quickly brown the leberknödel in a little duck, or other, fat. Drain on absorbent paper.

The cooked leberknödel benefit from a sauce. I’ll probably try a simple mustard-cream sauce next, but you could used just about any sauce you desire. The clear sauce I used for the picture is listed below.

60 ml (1⁄4 c)

dry vermouth

2 g (1 t)

kuzu starch, ground to a powder in a mortar

1. Place the wine and starch in a small saucepan over medium heat. Stir to distribute the starch, and continue stirring as required until the liquid is bubbling and the starch has thickened the wine.

© 2013 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.